Improving Women’s Health: HIV, Contraception, Cervical Cancer, and Schistosomiasis

Reported by:

Pinelopi Kyriazi

Presented by:

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS)

The New York Academy of Sciences

Overview

Approximately 36.7 million people currently live with HIV worldwide. Successful treatment with antiretroviral therapy has controlled the virus and prevented transmission in more than 20 million people. However, barriers to treatment and prevention such as stigma and discrimination, especially against women, are still prevalent in the communities most affected by HIV. According to the United Nations, an integrative strategy is required, not only in response to HIV, but also for the advancement of women’s sexual and reproductive health and rights. To accomplish this, they have focused on three main areas of intersection between HIV and women’s health: hormonal contraception, cervical cancer, and female genital schistosomiasis (FGS). Recent scientific advances raise the possibility of enhancing women’s health through closer collaboration and engagement between women, their health care providers and health programmers, and policy makers.

On March 15, 2018, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), the World Health Organization (WHO), and the Microbiology & Infectious Diseases Discussion Group at the New York Academy of Sciences presented Improving Women’s Health: HIV, Contraception, Cervical Cancer and Schistosomiasis. Coinciding with the 62nd session of the UN, the daylong symposium focused on improving women’s health in line with the UN Sustainable Development Goals designed to broaden community response to HIV and identify methods of intervention and treatment for reproductive diseases that afflict women.

Speakers

Sharon Achilles, MD, PhD

University of Pittsburgh

Shona Dalal, PhD

World Health Organization

Jennifer Downs, MD, PHD

Weill Cornell Medical College

Danielle Engel, MA

United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA)

Mary Rose Giattas, MD

Jhpiego

Ebony Johnson, MHS

Global Coalition on Women and AIDS, Athena Network

Eyrun Kjetland, MD, PhD

University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

Erna Milunka Kojic, MD

Mount Sinai St. Luke’s, Mount Sinai West

Terry McGovern, JD

Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health

Pragna Patel, MD

US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Chelsea Polis, PhD

Guttmacher Institute

Nelly Rwamba Mugo, MD

Kenya Medical Research Institute

Vikrant Sahasrabuddhe, MBBS, MPH, DrPH

National Cancer Institute, NIH

Annah Sango

Zimbabwe Young Positives

Sponsors

Additional support provided by a medical education grant from Gilead

Session 1: Setting the Scene

Speakers

Terry McGovern, JD

Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health

Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

Terry McGovern, of the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University, introduced the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set by the UN and aimed at ending poverty by tackling a range of social and economic issues, including gender inequality. As a poverty lawyer in the late 1980s, McGovern witnessed first-hand human rights violations against women with HIV, including refusal to provide health benefits. “Science is affected by structural barriers,” said McGovern. At the time, “science had overlooked converging epidemics.” Today, the intersection between HIV and women’s healthcare, including hormonal contraception, cervical cancer, and female genital schistosomiasis continues to pose a problem in countries around the world. The purpose of this meeting was to raise awareness and promote efforts to end gender inequalities, empower women and girls, and to highlight the co-infections of HIV and female reproductive illnesses.

Speaker Presentation

Session 2: HIV and Cervical Cancer

Speakers

Danielle Engel, MA

United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA)

Mary Rose Giattas, MD

Jhpiego

Ebony Johnson, MHS

Global Coalition on Women and AIDS, Athena Network

Erna Milunka Kojic, MD

Mount Sinai St. Luke’s, Mount Sinai West

Vikrant Sahasrabuddhe, MBBS, MPH, DrPH

National Cancer Institute, NIH

Annah Sango

Zimbabwe Young Positives

The Intersection of Cervical Cancer and HIV

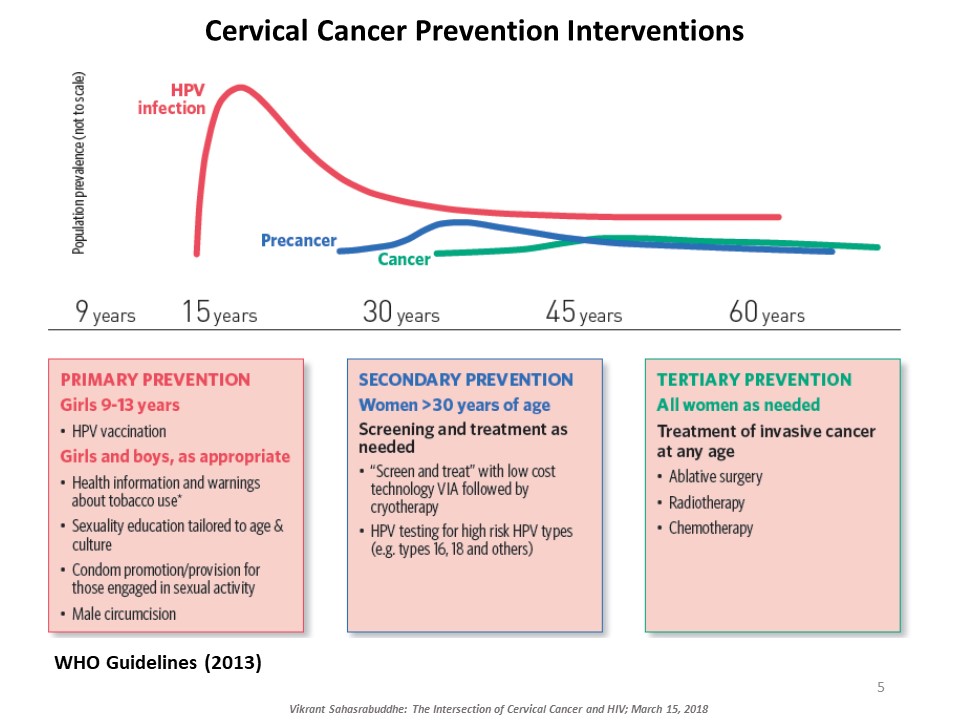

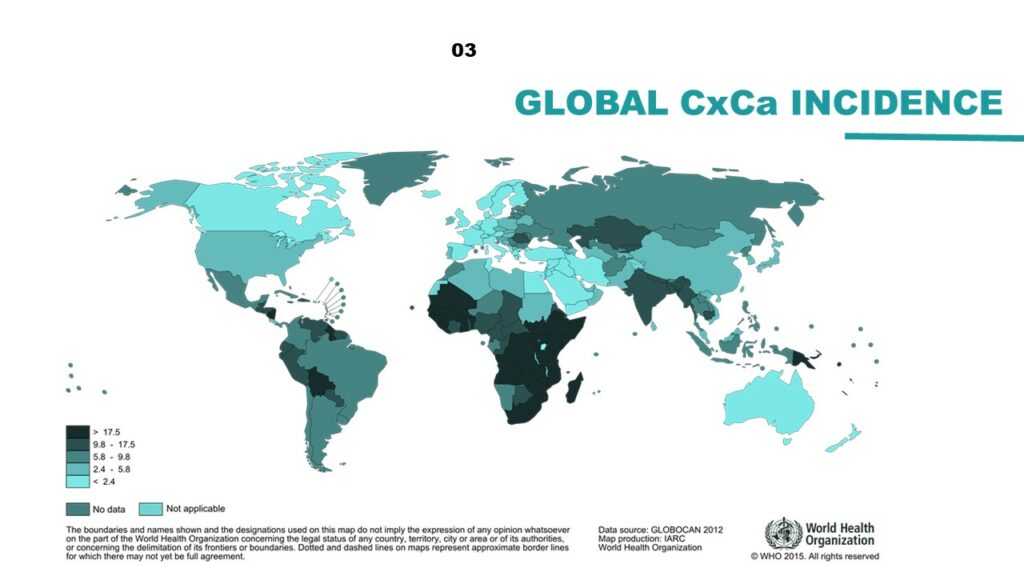

Vikrant Sahasrabuddhe, of the National Cancer Institute at the NIH, explained the intersection of cervical cancer and HIV. Cervical cancer, caused by oncogenic genotypes of the human papillomavirus (HPV), is a leading cause of cancer-related morbidity and mortality among women globally. HIV-infected women have three to five times higher risk for HPV-induced cervical lesions to progress to invasive cervical cancer. Millions of women with HIV now access affordable antiretroviral therapy globally and are living long enough for cervical cancer to manifest and progress. There are several approaches to prevent cervical cancer, including HPV vaccination and early detection and treatment of cervical precancerous lesions. Sahasrabuddhe talked about efforts underway to innovatively expand cervical cancer prevention services globally piggybacking on infrastructures developed through HIV care and treatment programs. ‘Screen-and-treat’ strategies use a low-cost simple clinical innovation called visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) to detect precancerous lesions, followed by either freezing of the lesions by cryotherapy or referral of women with larger lesions for further evaluation and excisional treatment. Rapid, point-of-care HPV tests with self-collection of samples are being introduced for improving the sensitivity of VIA-based screening, although testing costs are still a barrier. Sahasrabuddhe concluded by emphasizing the need for improving current interventions and provided an overview of efforts for evaluating reduced dosing of HPV vaccines, improvements in screening accuracy via technological advancements, and novel non-surgical alternatives for treating precancer.

HPV Vaccine and HIV in Women

Erna Mulinka Kojic, of Mount Sinai St. Luke’s, continued the conversation on HIV and HPV co-infections. She pointed out that cervical cancer is not the only known cancer caused by HPV. For example, HPV also causes oropharynx, anal, oral cavity, larynx, vulva, and penile cancers but they have been neglected in the field, resulting in a lack of national recommendations for screening methods. Kojic then shifted the focus to HPV vaccines, which consist of virus-like particles housed in empty shells that are specific to HPV types. This specificity makes it difficult to create one vaccine for treating all nine types of HPV. Efficacy trials of the current quadrivalent HPV vaccine –which targets HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18—indicate that it is 98% effective in preventing cervical cancer. However, in individuals previously infected with HPV types 16 or 18, the efficacy drops to 44% and even further to 17% in those with a history of any other type of HPV. Hence, the goal is to vaccinate boys and girls between the ages of 9-26 to catch cases before infection occurs. In a study on the immunogenicity of the quadrivalent HPV vaccine in HIV+ women, Kojic and colleagues found the vaccine to be highly safe and effective among this population. Vaccinated women showed a large increase of antibody titers compared to pre-inoculation levels, indicating the success of the vaccine. These exciting results present the possibility that the vaccine can do more than prevent HPV in uninfected individuals but also protect HIV+ women.

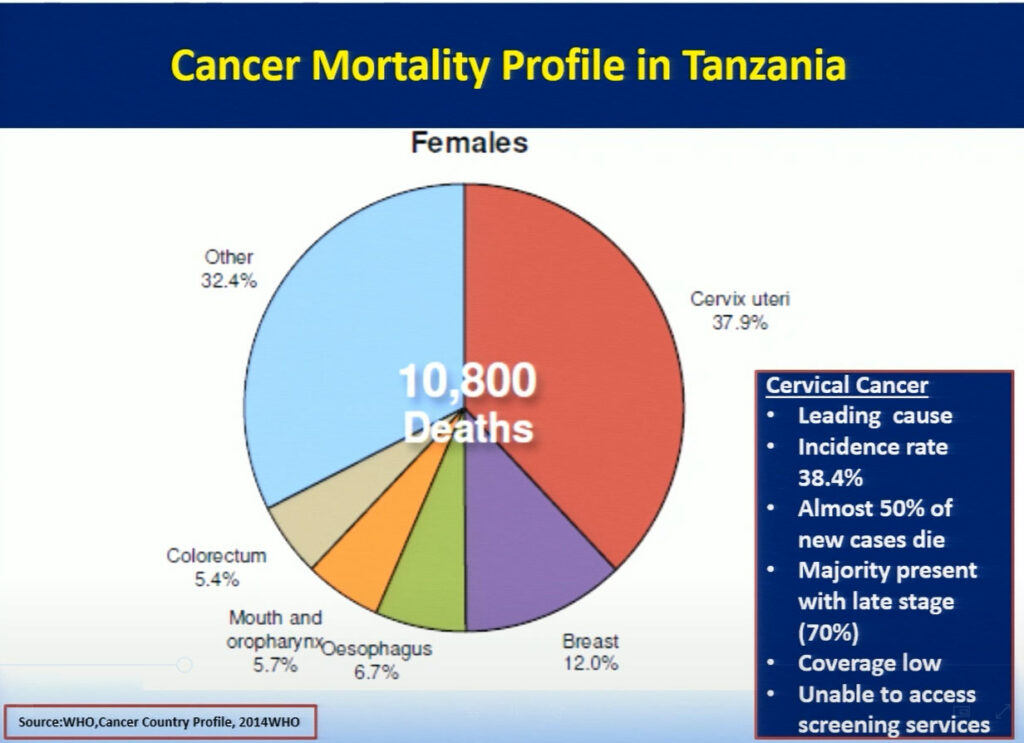

Bending the Curve for Cervical Cancer Prevention in Tanzania-Reflections on Effective Programming for Population Coverage

Mary Rose Giattas, of Jhpiego (a Johns Hopkins University affiliate), reflected on the challenges Tanzania faced while developing a national program for cervical cancer prevention (CECAP). The combination of Tanzania’s high incidence rate of cervical cancer, a large pool of adult women with HIV infection, and the lack of CECAP services provided in rural areas where more than 71% of the population lives, led the Tanzanian ministry to improve cancer services throughout the nation. In 2008, the Reproductive Health Cancer Unit was established with the goal to ensure women are free of cervical cancer. Through the support of the WHO and Merck, in collaboration with cervical cancer program implementing partners Tanzania developed a strategic plan focusing on the WHO’s three pillars of prevention. Jhpiego with USG funded MAISHA program provided technical inputs in the development process. While this plan has allowed doctors to successfully treat patients with small lesions using cryotherapy, the limited supply of LEEP devices creates a challenge in treating patients with larger lesions. Hence, collaboration between the Tanzanian ministry and Jhpiego, an international non-profit health organization with USG funding, has helped to further strengthen the key health system components in the program with the focus on the same day screening and treatment . Jhpiego has also been providing technical assistance to other implementing partners to improve access and quality of cervical cancer prevention services including timely and appropriate referral. Strong partnership between the MOH and implementing partners has contributed to scale up high quality VIA and Cryotherapy services for women with cervical cancer. In the 9 years since it was first implemented, this program has increased the number of CECAP sites from 3 to 557, improved cervical cancer and HIV testing, and reached more than 600,000 women in Tanzania. Bending the curve for cervical cancer prevention in Tanzania requires improving coverage by providing greater access to services through health system strengthening led by an empowered MOH, which has taken on the task of eliminating cervical cancer in Tanzania.

How Does Science and Delivery Affect People in Communities?

Following the incredible milestones of Tanzania’s health services, Annah Sango, of the Zimbabwe Young Positives, spoke about the harsh realities women in Zimbabwe face when seeking medical treatment for HIV. Some common issues include long lines at doctors’ offices due to limited supplies, low accessibility of healthcare providers in rural areas, and the stigma prevalent throughout the community. She advocated for more information on medical treatments, more access to care in both urban and rural areas, the need to involve and educate young boys and men, and friendlier doctors who provide unbiased treatment. Government collaborations with health organizations, similar to the programs Tanzania successfully implemented, would greatly benefit the Zimbabwean community.

The United Nations Joint Global Programme on Cervical Cancer

Danielle Engel, of the United Nations Population Fund, presented the development of a new, five-year Joint Programme at the UN, which seeks to eliminate cervical cancer globally. Given that we know how to treat cervical cancer and the prevention is cost effective, the greatest obstacle is making treatment widely available, especially in middle- and low-income nations with the highest incidence rates. The Programme is based on three pillars: prevention, treatment, and care. At the national level, the goals are to increase HPV immunization access to all girls, ensure screening and treatment for cervical pre-cancer by providing technical assistance to local governments, and guarantee universal access for the diagnosis and treatment of invasive cervical cancer. At the global level, new innovative technologies are needed for cervical cancer screening, as well as policies to improve and increase access to HPV vaccination.

Women, HIV, HPV and Cervical Cancer: An Intersectional Approach Moving beyond the Biomedical Lens

Although technological advances have enabled a needed reduction of new HIV infections, these advances are hampered by policy, funding, and access barriers in many parts of the world. Ebony Johnson, from the Global Coalition on Women and AIDS, Athena Network, gave a compelling call to action, emphasizing the need to go beyond the biomedical to include a human rights lens in the creation of enabling environments for healthy women and girls. As part of the Athena Network’s global #WhatWomenWant campaign, Johnson and colleagues asked women and girls around the world what they need to be safe, healthy, educated, and empowered in their communities. Participants said they want respect, representation, equal opportunities, power and autonomy over their own bodies, and much more. Johnson advocated for women and girls to be a part of research at the onset and for doctors to communicate better with their patients, creating bi-directional interactions and suspending judgment. “[Women] know our bodies, we know our communities, we know our environments, we know our barriers,” said Johnson, “and we know how to help you help us.” Ultimately, expanding funding, igniting political will, promoting intersectional sexual and reproductive healthcare, and developing innovative HIV, HPV and cervical cancer programming are key components of achieving gender equality.

Speaker Presentations

Further Readings

Sahasrabuddhe

Schiffman M., Doorbar J., Wentzensen N., et al.

Carcinogenic human papillomavirus infection.

Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2016 Dec; 2:16086. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.86.

Sahasrabuddhe V.V., Parham G.P., Mwanahamuntu M.H., Vermund S.H.

Cervical cancer prevention in low- and middle-income countries: feasible, affordable, essential.

Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2012 Jan;5(1):11-7.

Sankaranarayanan R., Wesley R.S.

A practical manual on visual screening for cervical neoplasia.

IARC Manual. 2003.

Parham G.P., Mwanahamuntu M.H., Kapambwe S., et al.

PLoS One. 2015 Apr; 10(4):e0122169.

Gelband H., Sankaranarayanan R., Gauvreau C.L., et al.

Lancet. 2016 May; 387(10033):2133-2144.

Mwanahamuntu M.H., Sahasrabuddhe V.V., Kapambwe S., et al.

PLoS Med. 2011 May;8(5):e1001032.

Parham G.P., Mwanahamuntu M.H., Pfaendler K.S., et al.

eC3–a modern telecommunications matrix for cervical cancer prevention in Zambia.

J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2010 Jul; 14(3):167-73.

Sigfrid L., Murphy G., Haldane V., et al.

Integrating cervical cancer with HIV healthcare services: A systematic review.

PLoS One. 2017 Jul; 12(7):e0181156.

Kojic

Bosch F.X, Manos M.M., Munoz, N. et al.

J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995 Jun 7;87(11):796-802.

Kojic E.M., Cu-Univ S., Conley L., et al.

Sex Transm Dis. 2011 Apr; 38(4):253-9.

Pinto A.P., Crum C.P.

Natural history of cervical neoplasia: Defining progression and its consequence.

Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2000; 43:352–362.

De Sanjose S, Quint WGV, Alemany L, et al, for the Retrospective International Survey and HPV Time Trends Study Group.

Lancet Oncol 2010; 11: 1048–56.

Serrano B., Alemany L., Tous S. et al.

Potential impact of a nine-valent vaccine in human papillomavirus related cervical disease.

Infect Agent Cancer. 2012; 7:38.

The FUTURE II Study Group.

Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent high-grade cervical lesions.

N Engl J Med. 2007; 356:1915-1927.

Kojic E.M., King M., Cespedes M.S., et al.

Immunogenicity and safety of the quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine in HIV-1-Infected women.

Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2014; 59(1): 127-135.

Session 3: The Right to Comprehensive Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights

Speakers

Peter Godfrey-Faussett

UNAIDS

Sharon Achilles, MD, PhD

University of Pittsburgh

Shona Dalal, PhD

World Health Organization

Ebony Johnson, MHS

Global Coalition on Women and AIDS, Athena Network

Nelly Rwamba Mugo, MD

Kenya Medical Research Institute

Chelsea Polis, PhD

Guttmacher Institute

Vikrant Sahasrabuddhe, MBBS, MPH, DrPH

National Cancer Institute, NIH

Annah Sango

Zimbabwe Young Positives

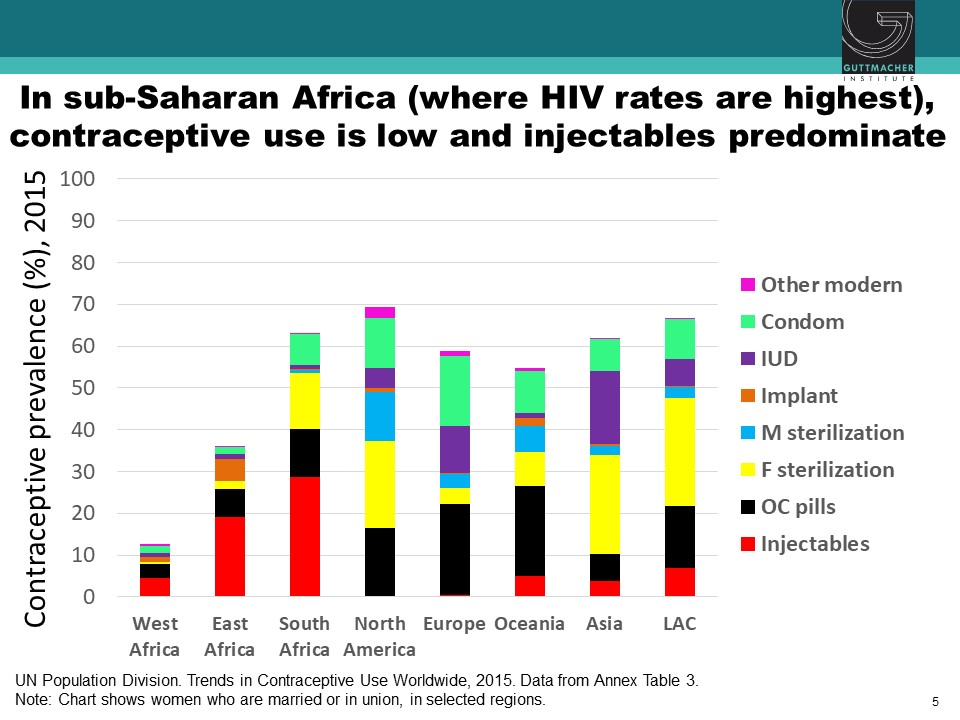

Hormonal Contraceptive Methods and Women’s Risk of HIV Acquisition: Understanding the Evidence

Observational studies have suggested an association between use of specific hormonal contraceptives (HCs), particularly the injectable depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA), and increased risk of HIV acquisition in women. This issue is critically important for women’s health, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, where high rates of HIV coincide with high use of injectable contraception. Chelsea Polis, from the Guttmacher Institute, presented the results of a comprehensive review she conducted with her colleagues on the relationship between HC methods and HIV risk. The preponderance of data for oral contraceptive pills, injectable norethisterone enanthate, and levonorgestrel implants do not suggest an association with HIV acquisition, though data for some of these methods were limited. On the other hand, new information increases concerns about a potential causal association between DMPA and HIV acquisition risk in women, although the possibility of confounding in these observational data cannot be excluded. Since DMPA is the most commonly used type of birth control in sub-Saharan Africa, these results could have important implications for these epidemiological populations. A meta-analysis estimated that DMPA may increase a woman’s risk of HIV acquisition by about 40%. In other words, if the association between DMPA and HIV is causal, a woman with a 2.4% chance of HIV per year would increase her risk to 3.3% if she uses DMPA. Similarly, a woman who starts at a higher baseline risk, for example, 14% per year, would increase her risk to about 19% per year if she uses DMPA. While these studies suggest a potential causal association between DMPA and women’s risk of HIV, all currently available data are observational, and thus potentially vulnerable to confounding. A randomized study is underway to attempt to parse out the relationship between various HC methods and women’s risk of HIV acquisition.

Hormonal Contraception and HIV Acquisition Risk: Biological Plausibility, Clinical Evidence, and Research Gaps

Sharon Achilles, of the University of Pittsburgh, addressed the biological evidence for the possible mechanisms of action of HCs in HIV-infected individuals. She focused on four main mechanisms, including: changes in architectural epithelial cells, target cells, immune changes, and microbiota. Architectural changes of epithelial cell thinning were seen in animals given DMPA. However, similar studies in women failed to show significant thinning between the follicular and luteal cycles, which has led researchers to nearly abandon this mechanism of action. Evidence for target cell changes in healthy HIV- women on DMPA showed increased cervical CD8CCR5+ target cells during high progestin concentrations, which was not evident in women using Net-En, an alternative injectable contraceptive. Studies on adaptive and innate immune changes have provided variable results making it difficult to converge on a specific mechanism. Finally, none of the hormonal methods shifted the vaginal microbiota studied including Lactobacilli, Gardnerella, and Atropobium vaginalis. Achilles cautioned that the study of biological changes associated with HC is complicated by the diversity of available hormones and delivery routes. There is a need for more precise categorization of progestin types, progestin concentration, and mode of administration to converge results from multiple studies and understand the biological mechanisms linking HCs to HIV.

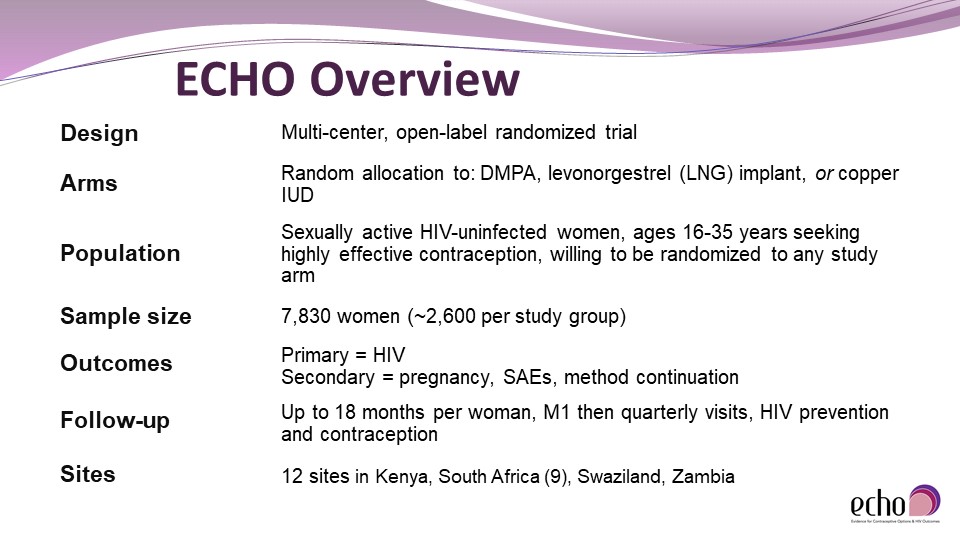

Update on the Evidence for Contraceptive Options and HIV Outcomes (ECHO) Trial

Given the lack of a causal link between DMPA and HIV risk, the Evidence for Contraceptive Options and HIV Outcomes (ECHO) trial was created to fill this critical knowledge gap. Nelly Rwamba Mugo, of the Kenya Medical Research Institute, provided an update and overview of the trial. As an open-label randomized clinical trial for HCs, ECHO has recruited more than 7,800 women, ages 16-35, in four countries since it began in 2015. Participants were randomly assigned to one of three types of birth control: DMPA, levonorgestrel (LNG) implant, or copper intrauterine device (IUD), and regularly tested over 18 months for HIV and pregnancy. Furthermore, participants were given contraceptive and HIV-risk reduction counseling. The results of the study, expected within the next year, will indicate HIV incidence, pregnancy rates, serious adverse events (SAEs), and method continuation associated with each of the three HCs. This information will help policymakers formulate counseling options for clinicians and educate women and communities on the benefits and risks of using the three contraceptive methods.

Translating Evidence to Policy: Guidance on Hormonal Contraceptive Use for Women at High Risk of HIV

Shona Dalal, of the World Health Organization (WHO), reviewed the Medical Eligibility Criteria (MEC) used by the WHO to provide recommendations on 25 methods of contraception. Based on the review of various hormonal contraceptive methods and HIV conducted by Chelsea Polis and colleagues, the WHO changed the classification for progestogen-only contraceptives for women at high risk for HIV from no restriction, to an indication that the advantages of this method generally outweigh the theoretical risks. In reassessing the risk level, they considered the following: quality of the evidence (GRADE profile), values and preferences of contraceptive users and providers; balance of benefits and harms; priority of the problem; equity and human rights; acceptability; and feasibility. Although there continues to be evidence of a possible increased risk of contracting HIV among progestogen-only injectable users, there is an absence of evidence from randomized trials and unclear causality (methodological issues versus a real biological effect). Dalal stressed that messaging surrounding possible risk is critical so that women at low risk of HIV infection don’t change their preferred method of contraception. “The WHO is committed to keeping emerging evidence under close review,” said Dalal, before explaining that data from the ECHO trial is highly anticipated so that the WHO can incorporate it into future guidance accordingly.

Panel Discussion: Integrating Rights, Services and HIV

The first panel discussion addressed the impending results of the ECHO trial and its impact on the communities that use DMPA. Peter Godfrey-Faussett from UNAIDS moderated the conversation, which included four of the speakers: Annah Sango, Ebony Johnson, Nelly Rwamba Mugo, and Vikrant Sahasrabuddhe. The panelists warned that African communities rely heavily on DMPA for contraception and it is vital that they are informed early about the possible outcomes of the study and how to proceed. Education about alternative methods of contraception should come from a collaborative partnership between patients and healthcare providers rather than media outlets. This can prevent fear and overgeneralizations of HIV risk to other types of birth control which may not apply.

Panelists also discussed the intersection of HPV, contraceptives, and cervical cancer. Sahasrabuddhe noted that the literature on HCs and HPV acquisition is mixed but oral contraceptives tend to increase risk of HPV. Yet the studies conducted on these co-factors are mostly observational and should be revisited. On the other hand, the known progression of HPV to cervical cancer provides opportunities for developing better screening techniques and possibly a single dose, multivalent vaccine that would protect against 98% of HPV types. The session closed with take-home points emphasizing the need for better doctor-patient interactions, good policies translating to good practice, and keeping the public scientifically educated.

Speaker Presentations

Further Readings

Polis

Polis C.B., Curtis K.M.

Lancet Infect Dis. 2013 Sep;13(9):797-808.

Polis C.B., Phillips S.J., Curtis K.M., et al.

Contraception. 2014 Oct;90(4):360-90.

Polis C.B., Curtis K.M., Hannaford P.C., et al.

AIDS. 2016 Nov 13;30(17):2665-2683.

Riley E.M.H, Steyn P.G., Achilles S.L., et al

Hormonal contraceptive methods and HIV: research gaps and programmatic priorities

Contraception. 2017 Aug;96(2): 67-71.

Polis C.B., Achilles S.L., Hel Zdenek, Hapgood, J. P.

Contraception. 2018 Mar; 97(3): 191-137.

Achilles

Stanczyk F.Z., Hapgood J.P., Winer S., Mishell D.R. Jr.

Endocrine Reviews. 2013 Apr;34(2):171-208.

Quispe Calla N.E., Vincetti Miguel R.D., Boyaka P.N., et al.

Mucosal Immunology. 2016 9, 1571-1583.

Byrne E.H., Anahtar M.N., Cohen K.E., et al.

Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 Apr;16(4):441-8.

Mitchell C.M., McLemore L., Westerberg K., et al.

J Infect Dis. 2014 Aug 15;210(4):651-5.

Achilles S.L., Austin M.N., Meyn L.A., et al.

Impact of contraceptive initiation on vaginal microbiota.

Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Mar 2. pii: S0002-9378(18)30176-5.

Session 4: Female Genital Schistosomiasis (FGS)

Speakers

Jennifer Downs, MD, PHD

Weill Cornell Medical College

Eyrun Kjetland, MD, PhD

University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

Pragna Patel, MD

US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Female Genital Schistosomiasis: A Burning Sensation, Malodorous Discharge and Bleeding from a Waterborne Parasite

The final session of the symposium shifted towards the intersection of HIV and Female Genital Schistosomiasis (FGS). Eyrun Kjetland, from the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, explained that urogenital schistosomiasis, a largely African, waterborne, parasitic disease that can cause Female Genital Schistosomiasis (FGS), affects the cervix, fallopian tubes, and the urinary tract. The cycle of FGS begins with eggs released with urine or feces in fresh water rivers or lakes. These eggs hatch, releasing larvae that infect snails and multiply into many cercariae parasites. The parasites then penetrate human skin and lay eggs inside the body, which typically penetrate the cervix and appear as grainy, sandy patches on the vaginal wall. In a cross-sectional study in a Zimbabwean community, 41% of women with FGS were also HIV+. Importantly, FGS, which may mimic the symptoms of cancer and sexually transmitted infections is not limited to adult women. Young girls aged 10-12 typically contract it and can develop symptoms including: intravaginal lesions, malodorous discharge, bloody discharge, a burning sensation in the genitals, and ulcers. Affected young girls grow into adulthood with damaged genitals and may experience infertility and ectopic pregnancy. Starting treatment at a young age can help reduce contact bleeding and decrease CCR5-HIV receptor expression in CD4+ cells, a receptor used by HIV to enter and infect host cells.

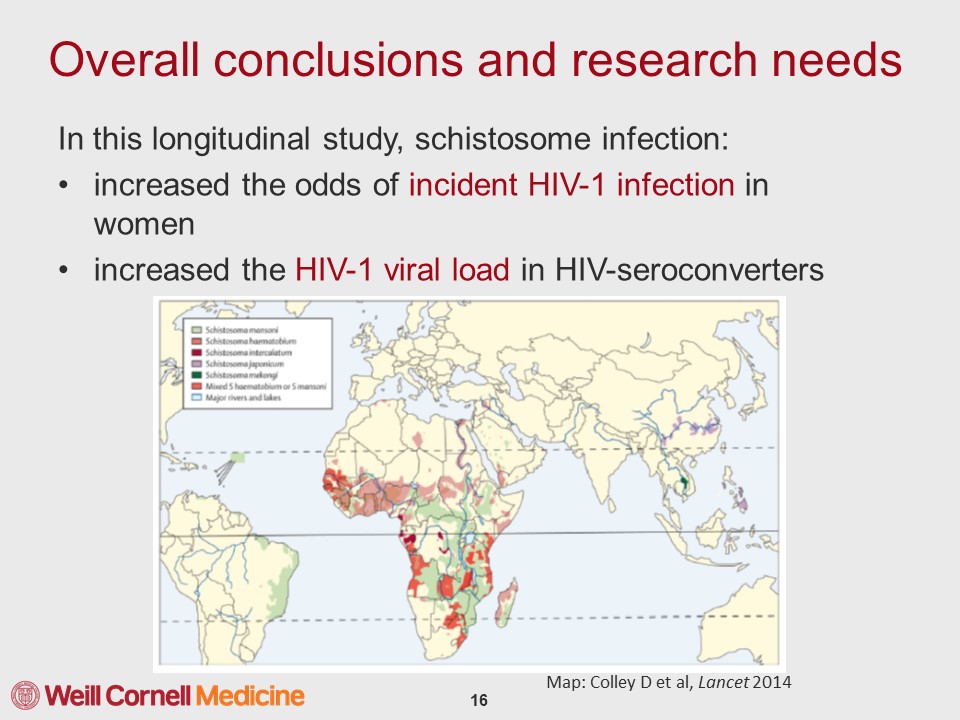

HIV and Schistosomiasis: Summary of the Evidence

Jennifer Downs, of Weill Cornell Medical College, summarized evidence from epidemiological studies in sub-Saharan Africa on the relationship between FGS and HIV. To date, three studies have found an increased odds of being HIV-infected of at least 2.9 in women with FGS by measuring either parasite eggs or circulating anodic antigen, a carbohydrate produced in the gut of adult schistosome worms. A similar study in men failed to find a significantly increased odds of HIV infection, highlighting that the intersection between schistosomiasis and HIV specifically affects women. Work done in macaque monkeys with pre-existing Schistosoma mansoni infections showed that when they were rectally inoculated with increasing doses of simian HIV (sHIV), they became sHIV-infected at a dose 17 times lower than macaques without schistosomiasis. Furthermore, the monkeys infected with Schistosoma mansoni showed increased HIV viral replication. Downs reported results from a nested case-control study situated within a longitudinal study in adults of reproductive age since 1994 in Kisesa, Tanzania. In the longitudinal study, participants are tested for HIV every three years and have blood spots stored for additional analyses, allowing researchers to compare individuals who recently contracted HIV to matched controls that didn’t contract HIV during this period. Downs and colleagues documented that the prevalence of the schistosome infection at the time of HIV-seroconversion was higher among HIV-1 female seroconverters but not males. Seroconverters with schistosome infection also have higher HIV-1 RNA levels at the time of HIV diagnosis. Hence, this study has been vital in extending findings on schistosomiasis from animal models to humans.

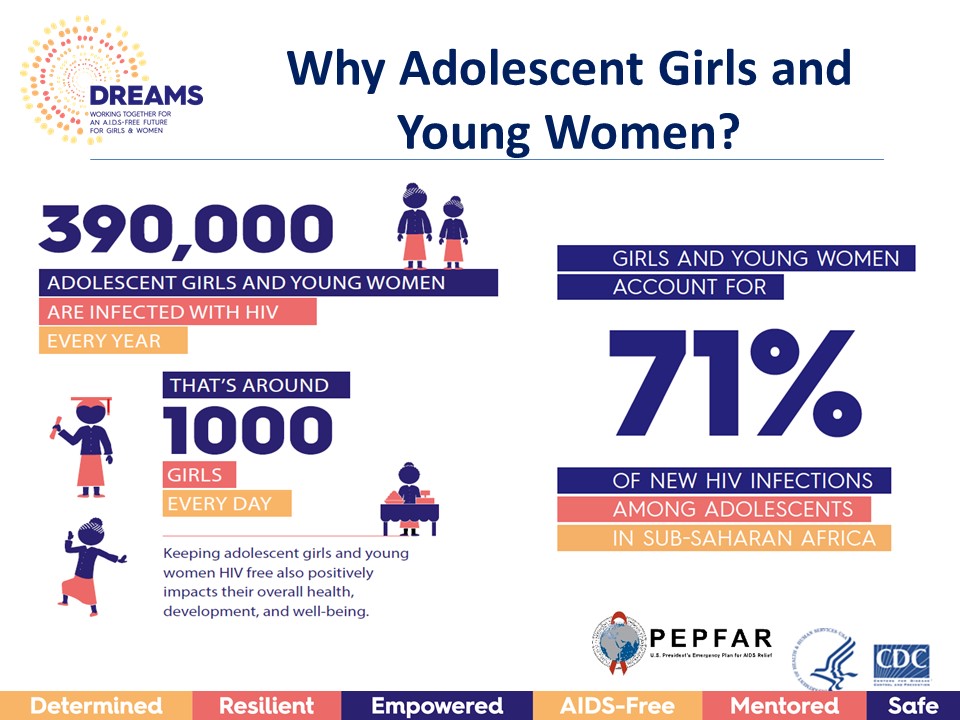

Schistosomiasis and HIV Transmission: A Call for Research

The dearth of research on schistosomiasis and HIV transmission is a problem for this largely African epidemic. Schistosomiasis affects more than 230 million people worldwide, 90% of whom are in Africa. Pragna Patel, of the CDC, highlighted that there is not enough epidemiological evidence in terms of incidence and prevalence of FGS and HIV. Furthermore, due to decreasing child mortality, the youth population in sub-Saharan Africa will double by 2020 from the start of the HIV epidemic in 1990. This increase in the size of vulnerable populations and the fact that young girls typically contract FGS through freshwater contact with recurrent exposures throughout their lifespan, requires improved treatment of FGS to reduce HIV infections in the future. Patel made a call for research on the effect of FGS and its treatment on HIV acquisition, particularly among adolescent girls and young women.

Next Steps: Research, Policy, Activism

The final session ended with an open discussion in which audience members dove deeper into the current understanding of schistosomiasis by asking questions on its transmission and overlap with HIV. The speakers noted that while men are less likely to have schistosomiasis, those who do, tend to have bloody semen, making it more likely that they transmit HIV. This intersection with HIV can be leveraged to provide more widespread treatment of schistosomiasis. Kjetland mentioned a current randomized trial she is conducting in African communities which uses a thorough questionnaire to identify potential confounds in kids with schistosomiasis. Such trials can catch cases at an early stage and provide consistent treatment. Downs called attention to the WHO guidelines for treating schistosomiasis, which indicate that in communities with prevalence above 50%, treatment should be provided twice a year to all community children. Yet, less is done to diagnose and treat adults with schistosomiasis. Pragna mentioned that the DREAMS initiative for adolescent girls and young women, which is currently implemented in a number of African communities, could be anchored to create an integrative package to educate women on HPV, cervical cancer, HIV, and schistosomiasis. These types of initiatives along with good policies can greatly reduce prevalence and stigma of female-reproductive diseases around the world.

Speaker Presentations

Further Readings

Kjetland

Kjetland E.F., Ndhloyu P.D., Gomo E., et al.

Association between genital schistosomiasis and HIV in rural Zimbabwean women.

AIDS. 2006 Feb 28;20(4):593-600.

Kjetland E.F., Kurewa E.N., Ndhlovu P.D., et al.

Trop Med Int Health. 2008 Dec;13(12):1509-17.

Kjetland E.F., Norseth H.M., Taylor M., et al.

Classification of the lesions observed in female genital schistosomiasis.

Int J Obs Gyn. 2014 127(3).

Appleton C.C., Madsen H.

Human schistosomiasis in wetlands in southern Africa.

Wetlands Ecology and Management. 2012 20(3): 253-269.

Hegertun I.E.A., Gundersen K.M.S., Kleppa E., et al.

PLoS Negl Trp Dis. 2013 Mar; 7(3): e2104.

Kleppa E., Ramsuran V., Zulu S., et al.

PLoS One. 2014.

Norseth H.M., Ndhlovu P.D., Kleppa E., et al.

PLoS Negl Trp Dis. 2014.

Downs

Downs J.A., Mguta C., Kaatano G.M., et al.

Urogenital schistosomiasis in women of reproductive age in Tanzania’s Lake Victoria region.

Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011 Mar;84(3):364-9.

Downs J.A., van Dam G.J., Changalucha J.M., et al.

Association of Schistosomiasis and HIV infection in Tanzania.

Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012 Nov;87(5):868-73.

Downs J.A., de Dood C.J., Dee H.E., et al.

Schistosomiasis and Human Immunodeficiency Virus in Men in Tanzania.

Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017 Apr;96(4):856-862.

de Water R., Fransen J.A., Deelder A.M.

Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1986 May;35(3):549-58.

van Lieshout L., de Jonge N., Bassily S., et al.

Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1991 Mar;44(3):323-8.

van Dam G.J., Bogitsh B.J., van Zeyl R.J., et al.

J Parasitol. 1996 Aug;82(4):557-64.

Corstjens P.L., van Lieshout L., Zuiderwijk M., et al.

J Clin Microbiol. 2008 Jan;46(1):171-6.

Leutscher P.D., Ramarokoto C.E., Hoffmann S., et al.

Clin Infect Dis. 2008 Sep 15;47(6):775-82.

Chenine A.L., Shai-Kobiler E., Steele L.N., et al.

PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008 Jul 23;2(7):e265.

Siddappa N.B., Hemashettar G., Shanmuganathan V., et al.

PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011 Aug;5(8):e1270.

Patel

Patel P., Borkowf C.B., Brooks J.T., et al.

Estimating per-act HIV transmission risk: a systematic review.

AIDS. 2014 Jun 19;28(10):1509-19.

Baggaley R.F., Hollingsworth T.D.

J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015 Apr 15; 68(5): 594–598.

Bustinduy A., King C., Scott J., et al.

HIV and schistosomiasis co-infection in African children.

Lancet Infect Dis. 2014 Jul;14(7):640-9.