A Look At Human Enhancement Technologies

Recent advances in human enhancement technologies offer new opportunities to redesign ourselves.

Published May 15, 2018

By Marie Gentile, Mandy Carr, and Richard Birchard

Recent advances in human enhancement technologies offer new and unique opportunities to redesign ourselves. Such efforts have a long history, as people have been attempting to overcome their biological limitations or remove supposed flaws for millennia.

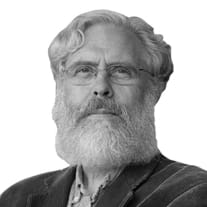

As George Church, PhD, from the Wyss Institute at Harvard University explained, before the 21st century human enhancements included anything from: vaccines preventing smallpox, polio, and measles; to cars and jets that moved people across the world at previously unimaginable speeds and distances; to the smartphone you may be reading this article on; and the cup of coffee you drink every morning to help wake up. Dr. Church believes that the latest human enhancement efforts in fields like gene editing and artificial intelligence are only following this well-trod path.

Human Enhancement Technologies

Eventually, Dr. Church suspects that human enhancement technologies could provide resistance to diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis, and Lyme disease, allow for up-to-date diagnostic readouts in healthcare, and even reverse aging. Advancement in genome editing technologies such as CRISPR could have the greatest impact by targeting, for example, human genes like CCR5 — an essential gene for HIV virus entry into target cell — and lead to a functional cure for HIV infection.

Such promises for the future of enhancement technologies are exciting, but not without potential risk. Critics have questioned the ethics of using these technologies to fundamentally alter human biology, and have called for careful investigations of the risks and potential complications before we can safely apply these new technologies. Moreover, there may be additional considerations if these new technologies are used for non-therapeutic purposes.

“If you have a sick person and you’re thinking about using a new drug to help them, risk is always tolerated — because the person’s life is at stake. But when you’re thinking about enhancement technology, it’s a slightly different risk-benefit calculus because that person isn’t necessarily dying or suffering, they’re receiving an enhancement,” says Josephine Johnston, LLB, MBHL from The Hastings Center.

The Ethics of Defining Enhancement Technologies

Additionally, she argued, “by definition, an enhancement technology claims to improve a person or a group of people. What it means to be improved, to be better, is very much a socially and culturally constructed notion. I would worry most about social pressure to conform to limited visions of the good and the improved, and our failure to adequately question and interrogate those visions.”

It is critical to discuss the principles that govern the ethical conduct of human enhancement. Dr. George Church stated that the NIH requires grantees to teach the responsible conduct of research to young scientists. He added that “most engineering disciplines have safety and security components and a code of ethics.”

However, Ms. Johnston maintained that individual scientists alone shouldn’t be required to focus on the ethics of the individual use of the technology they develop.

“I don’t think they should ignore it, but that’s not primarily the work that scientists are trained to do and it would be an unreasonable thing to place on [their] shoulders.” However, she continued, “I do think that it’s crucial for scientists as a collective group to be involved in discussions for developing policy.”

What Does it Mean to Be Human?

While there have been, and will continue to be major technology revolutions in human enhancement, Ms. Johnston believes that human enhancement raises long standing questions about what it means to be human.

“There are going to be upsides and downsides to these different enhancement technologies, but that complexity might be difficult to see at first and we might not agree on,” says Johnston. “How will we know when we’re seeing something that really, truly can improve people’s lives? These questions about what makes for a good — or even a better — life are questions we’ve been grappling with for a long time. I’m not sure that I see a brand new question. Just new iterations of old questions about what it means to live well.”

Also read: Teaming Up to Advance Brain Research.