Beyond the Beaches: Revealing the Real Puerto Rico I

Part One: Into the Unknown

Relatively little was known about the small Caribbean Island prior to a series of expeditions led by The New York Academy of Sciences in the early 20th century.

Published September 16, 2024

By Nick Fetty

Puerto Rico is known for its beautiful beaches, rich rainforests, and bioluminescent bays that attract tourists from all over the world.

Upon the conclusion of the Spanish American War in 1898, Puerto Rico (often spelled “Porto Rico” during this era) became an official territory of the United States. In the following years, the University of Puerto Rico was established. Academic and scientific institutions in the U.S. also began conducting their own field work on the island. Some scientific research had occurred prior to the Academy’s survey. However, these early findings were only available in obscure, generally inaccessible journals. Roads, harbors, and other infrastructure were also constructed during this era. This made the island, roughly three quarters the size of Connecticut, more navigable.

In 1912, The New York Academy of Sciences commenced planning its first in a series of scientific surveys of “Porto Rico”. Nathanial Lord Britton, a Fellow at the Academy and, later, Academy president, led many Puerto Rican expeditions. He initially proposed a four-year project with the Academy contributing $2,000 (roughly $63,000 today) annually.

Emerson McMillion was the Academy’s then-president and a Wall Street investment banker. He was so in favor of the effort that he contributed personal funds to support it. Other area institutions eventually joined the effort. This included the American Museum of Natural History, the New York Botanical Garden, Columbia University, and New York University.

The First Visit to the Island

According to historian Simon Baatz’s 2017 update to his seminal history of the Academy published in 1988, there were two reasons for why the Academy chose Puerto Rico. Not only was it “an unexplored territory that had the potential for interesting and worthwhile discoveries” but it also had “the presence of an administrative structure that would provide Academy scientists with invaluable logistical and technical assistance.”

In March 1913, Britton, who also served as director of the New York Botanical Garden, visited the island. He established connections with researchers at the university as well as with government officials. Britton pinpointed several shortfalls in the current research that he hoped the Academy scientists could fill.

He also wanted to show the residents of Puerto Rico that their government was justified in funding and supporting this effort. Britton offered to print copies of their survey for distribution in Puerto Rican schools and libraries. Additionally, he committed to contributing specimens uncovered during the survey to establish a natural history museum on the island.

The research teams, which began arriving in 1914, were to conduct comprehensive studies in areas like zoology, geology, and anthropology.

Studying the Island’s Zoology

Researchers from the Academy’s zoology department departed for the island in summer 1914 to study the region’s fauna. Some of them were affiliated with the American Museum of Natural History.

Roy W. Miner, an Academy Fellow, examined the marine invertebrates and myriopods in the waters off the main island. Harry G. Barber, from the New York Entomological Society, conducted a similar survey on insects and arachnoids. John T. Nichols, also a Fellow, investigated the ichthyology of the region.

In this era, the rank of “Fellow” was bestowed upon Academy members who were selected by other active members for their scientific achievement.

Geological Findings

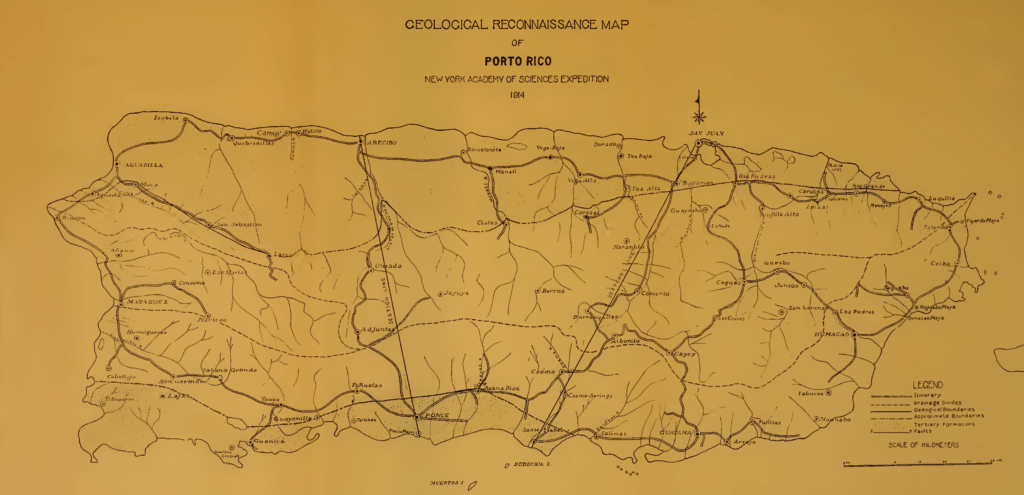

The geological work commenced in August 1914 and was led by Charles P. Barkey, then a vice president for the Academy who would go on to become president.

He traversed more than 2,000 kilometers across the island. His observations studied everything from hot springs and volcanic vents to rock formations and natural resources. These observations were recorded in the March 1915 issue of Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences (Annals).

“At the outset, it is well to appreciate that the Island of Porto Rico is geologically young. There are no traces, so far as known, of any of the so-called ancient rocks. It is quite true, of course, that the older series of formations is largely a volcanic complex whose exact age may never be accurately determined, but there is no occurrence of profoundly metamorphosed members or other evidences [sic] of great geologic age,” wrote Barkey.

Through an Anthropological Lens

Renowned anthropologist and Academy member Franz Boas began conducting field work in Puerto Rico in 1915. As an already established academic, he viewed the survey as an opportunity for his graduate students to conduct serious field work.

Boas and his research team scoured the island and interacted with locals to assemble “an immense collection of folk tales, riddles, ballads and songs.” The researchers also studied the anthropometric and dental features of school children in Utuado as well as soldiers in San Juan. The team’s archeological dig of “the ancient village of Capá” was perhaps their greatest contribution to the effort. The site is known today as Centro Ceremonial Indígena de Caguana.

The Importance of Communicating the Science

During these initial excursions, the research team brought back more than 200 specimens of water plants for gardens in New York City, according to The New York Times. Additionally, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported “some 12,000 fossils” were also brought back to New York.

According to Baatz’s 2017 book, the Academy’s initial efforts were considered so successful that “during the first two years, the Puerto Rico Survey expanded at an almost exponential rate so that by the summer of 1916, a total of twenty-three different groups had travelled to Puerto Rico to explore the botany, entomology, geology, ichthyology, mycology, anthropology, paleontology, and archeology of the island.”

Britton, who led these efforts, understood the importance of rapid dissemination of their findings. These findings were not only published by the Academy but also in the Journal of the New York Botanical Garden, the Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, and Science.

Academy affiliates and other researchers would make several visits to the Caribbean in the following years. Findings of the full survey were published through the 1940s as the Scientific Survey of Porto Rico and the Virgin Islands in 19 volumes. Additional reports would also appear in Annals. The Academy was continuing to prove its utility to the broader scientific community, and the efforts in Puerto Rico were just getting started in 1916.

This is the first article in a two-part series examining the Academy’s past expeditions to Puerto Rico. The series is part of National Hispanic Heritage Month.