Beyond the Beaches: Revealing the Real Puerto Rico II

Part Two: A Lasting Impact

What started off as a discovery excursion with many unknowns quickly yielded promise and proved to be one of The New York Academy of Sciences’ greatest early 20th century achievements.

Published October 1, 2024

By Nick Fetty

While celebrating its centennial in 1917, The New York Academy of Sciences also celebrated the success of one of its early scientific endeavors that still resonates today.

The Academy started planning a scientific expedition to Puerto Rico in 1912 and by 1914 the first groups of scientists were traveling to the island to begin conducting research. The findings from this field work were published in a 19-volume series titled The Scientific Survey of Porto Rico and the Virgin Islands. Much of the research was conducted and published in the early half of the 20th century, when relatively little was known about the region.

Expanding the Breadth of the Survey

Because of the success of the initial endeavor, the survey eventually expanded beyond the island of Puerto Rico to also include the Virgin Islands. Academy scientists observed “the physiography of the region was remarkably uniform,” according to historian Simon Baatz in the 2017 update to his seminal history of the Academy published in 1988.

The scientists reported three cycles of erosion in the area including Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. Baatz wrote: “The first cycle, which formed the ‘upper peneplane of Porto Rico’ was ended by uplift; the second cycle destroyed the earlier peneplane and ‘produced an old erosional surface approximately 700 feet below the first’; while the third cycle, which was terminated by submergence, resulted in the formation of a lower peneplane.” These fundamental geological structures are estimated to have been created during the conclusion of the Tertiary period.

Howard Meyeroff, a geology professor at Smith College, made several trips to the region in the 1920s. In The Scientific Survey of Porto Rico and the Virgin Islands he reported “the entire Porto Rico-Saint Croix-Virgin Islands area developed as a unit until the late Tertiary dissection of the coastal plain.” During this same era, other researchers would study the region’s mammalogy (mammals), mycology (fungi), and ornithology (birds).

“A 10,000-Acre Swamp Below Sea Level”

H.A. Gleason studied wetlands in Puerto Rico as part of the Academy’s expedition. Gleason was the curator of the New York Botanical Garden and was a pupil of Academy Fellow Nathanial Lord Britton as a doctoral student in taxonomy at Columbia University. While scientific in nature, Gleason’s Puerto Rican research also had an economic component.

Gleason studied a swamp along the north shore of Arecibo, largely surrounded by fertile cane fields. With sugarcane as a major export for the island, Gleason suggested draining the swamp so that the entire area could be used to cultivate this cash crop.

However, with the swamp being at sea level Gleason stated it cannot be drained using “ordinary means,” as reported by the Yonkers Herald. Instead, he suggested they’d need to follow the example of the Hollanders by “[building] dikes to keep out the sea, and then [draining] the swamp by means of pumps,” which could be powered by windmills because of near constant “trade winds.”

Gleason also observed differences in the island’s topography between the north and south. While the north is swampier and saw greater rainfall, the south is semi-desert, arid and is subject to “long periods of drought.”

Along with co-author Mel T. Cook, Puerto Rico’s government botanist and plant pathologist, this research was published in The Scientific Survey of Porto Rico and the Virgin Islands.

“Curious Habits of Birds”

The Smithsonian Institute’s Alexander Wetmore studied birds in the region in the late 1920s. He observed that the stomachs of the Antillean grebe would often “contain masses of their own feathers, plucked and swallowed, which are regularly ground up and passed on into the intestines,” he wrote in The Scientific Survey of Porto Rico and the Virgin Islands.

Wetmore also studied the honey-creeper. He didn’t have to travel far as the bird would often fly into the parlor of his hotel “to search the blossoms of cut flowers in vases,” according to reporting from the Roanoke World-News.

During these excursions into the hotel room, the bird became puzzled upon seeing its own reflection in the mirror. Wetmore wrote “As it fluttered before the glass, the bird on the opposite side always rose to meet it, and after several attempts to evade the reflection, first on one side and then on the other, it would drop down, baffled, and scold its image sharply with quickly flitting wings.”

Additionally, it was observed that female honey-creepers didn’t always appreciate the company of their male counterparts, particularly during nest building. As Wetmore wrote, “he brings materials only when the female is absent, for when she catches him in the nest, she immediately drives him out.”

Lastly, and perhaps most morbidly, Wetmore uncovered an interesting trait of the brown pelican, also referred to as an alcatraz. After speaking with locals, he discovered that “when the alcatraz grows old and feeble, rather than suffer death by starvation it commits suicide by hanging itself by the head from the fork of a mangrove or the crevice between two stones.”

Advancing the Archeology

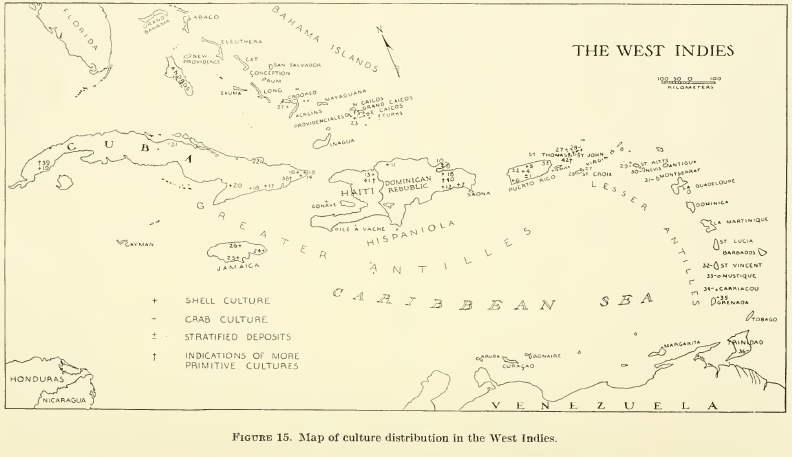

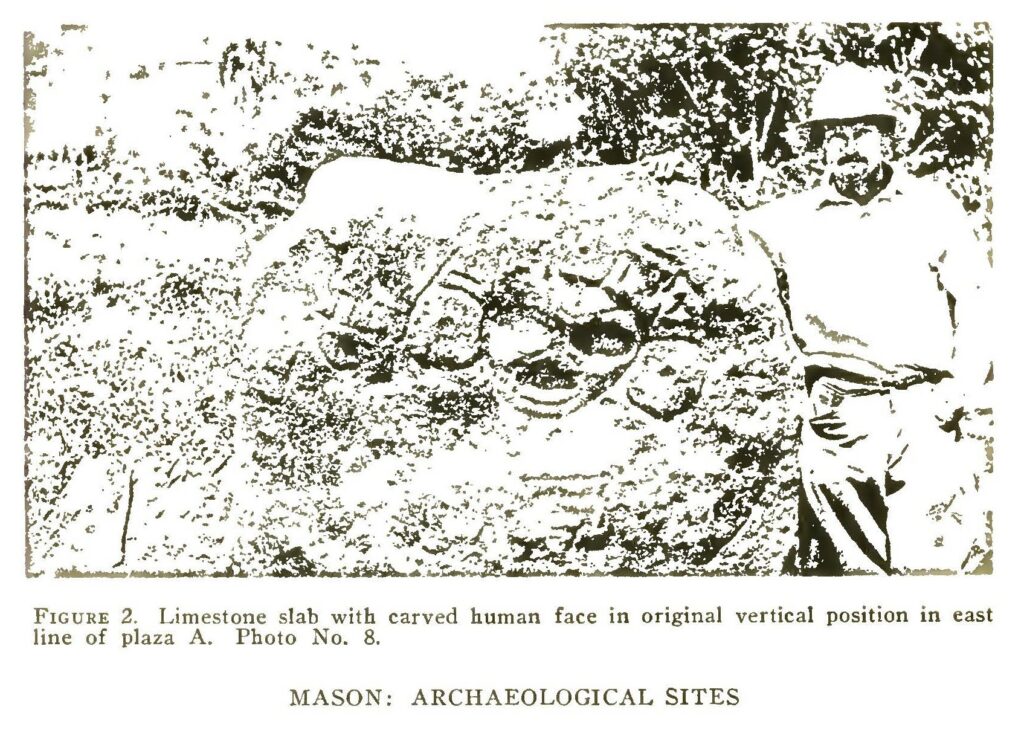

Researchers under the auspices of the Academy continued to conduct impactful archeological research in the region, eventually expanding to also cover other islands such as Cuba, Jamaica, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, the Bahamas and more by the 1930s.

On Puerto Rico, researchers in 1940 noted “[two] periods of prehistoric occupation on the island were distinguishable in clearly stratified deposits of culture refuse found on the north and south coasts.”

Done in multiple excavations across various parts of the island, the artifacts that researchers collected included decorative bowls, shell chisels, and carved stone figures.

The Puerto Rican Influence in NYC Today

Much of the success of this effort is attributed to Academy president Nathanial Lord Britton. What started as a four-year project in 1912, continued into the mid-1940s.

Britton controlled nearly every aspect of the survey until his death in 1934. Not only was he lauded for his organizational and administrative efforts, but he led what “proved to be the most ambitious project ever undertaken by The New York Academy of Sciences” so successfully that it became “an almost routine affair,” according to Baatz.

While Britton and other researchers from New York helped to influence the scientific culture in Puerto Rico, Puerto Ricans have influenced the culture in the city and other parts of the United States in various ways.

More than 1.1 million Puerto Ricans live in the New York Metropolitan Region, according to 2022 data. This influence has contributed to the city’s rich culture in everything from theatre (West Side Story, Hamilton) to music (Jennifer Lopez, Mark Anthony) to sports (Bernie Williams, Yankees; Carlos Beltrán, Mets).

This is the second article in a two-part series examining the Academy’s past expeditions to Puerto Rico. The series is part of National Hispanic Heritage Month.

Read: Part 1 – Into the Unknown.