Krainer Recognized for Pioneering Work in Anti-Sense Therapy

Dr. Krainer’s research examines anti-sense therapy and its application to spinal muscular atrophy.

Published December 15, 2020

By Melanie Brickman Borchard, PhD, MSc

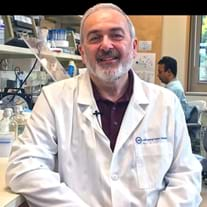

St. Giles Foundation Professor

at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

Photo credit: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

Adrian R. Krainer, PhD, St. Giles Foundation Professor at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, was awarded the 2020 Ross Prize in Molecular Medicine by the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research and Molecular Medicine for his pioneering work in introducing anti-sense therapy into clinical use and for its successful application to spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), an illness that has been the leading genetic cause of infant death.

“I was surprised to win the Ross Prize and really appreciate it,” remarked Krainer. “I view it as recognition of not just what I have done but of my whole team, which is the people currently in the lab and the ones that preceded them, plus our collaborators. It’s been a collective effort.”

Krainer emigrated from his native Uruguay to the United States in the late 1970s. He studied biochemistry and genetics at Columbia University. Later, during his graduate studies at Harvard, he became excited by a cutting-edge area of research—RNA splicing, a process that removes introns from precursor messenger RNA and joins the exons to enable translation of mRNA into a protein.

After working on the biochemistry of human RNA splicing, he was recruited to the Cold Spring Harbor Fellows Program upon graduation, where he focused on addressing basic mechanisms and regulation of splicing, what he referred to as, “curiosity-driven research, where we were just trying to learn something about how this process works and its natural regulation.”

Advancing Research on Spinal Muscular Atrophy

After spending fifteen years leading studies on the basic mechanisms and regulation of RNA splicing, in 1999 Krainer attended an invitation-only NIH symposium focused on SMA. This symposium was the catalyst for a revolutionary shift in the direction of his work. There, Krainer saw an opportunity to further elucidate the mechanisms he was already working on. He wanted to use this knowledge to find a potential therapy for SMA patients.

“Meetings are hugely important. Because of that meeting a little light bulb went off [related to the intersection of my work and SMA]. Not that I knew how we would solve the problem, but there was a realization that this problem fits really well with things we have been doing and is very worthwhile,” said Krainer.

A year later Krainer made a commitment to study SMA and by 2004 he entered into a partnership with Ionis Pharmaceuticals to focus on the development of Spinraza (generic name Nusinersen), the first FDA-approved drug to treat SMA associated with mutations in the SMN1 gene (approved in 2016). Since then, more than 11,000 people have been treated with this groundbreaking therapy.

“This is the best one can hope for as a researcher. It is really a dream come true that the basic research is translated into an actual drug that saves lives and is changing the quality of life for so many patients and families.”

Krainer added that the success of Spinraza has the potential to spiral outwards.

“It transcends this one disease, because it’s an example of what can be done with the antisense platform, now it can be used again and again for other neurological diseases and beyond.”

Reflecting on His Work

Today, Krainer continues to pursue the basic science aspects of splicing in his lab. Additionally, he seeks to refine the understanding of the complex machinery used for this process. Among other activities, his lab also focuses on antisense technology to develop therapies for other diseases caused by splicing defects and on understanding how splicing factors and dysregulated alternative splicing promote cancer progression.

Krainer sees being a scientist as a “privilege” and very much a collaborative effort wherein “everyone is doing something that they love.” Even so, he recognizes there are many bumps in the road for scientific discovery.

“One has to be very persistent,” he said. “I think that failure along the way comes with the territory. There’s a lot of troubleshooting and persistence required. If something doesn’t work, you try again or try in a different way. So, it’s a constant challenge and that’s part of the fun of the whole thing.”

The Ross Prize in Molecular Medicine was established in conjunction with the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research and the Springer Nature journal Molecular Medicine.

Read more about the Ross Prize and past awardees: