To Infinity: The New Age of Space Exploration

The business of space is in fashion again — or at least back in the news. Learn how space exploration today differs from the Sputnik era.

Published October 1, 2018

By Charles Ward

Academy Contributor

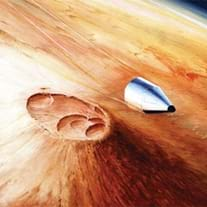

Fifty years ago, 2001: A Space Odyssey thrilled audiences with a vision of space travel, as a Pan Am space shuttle docked and delivered passengers to an international space station, all to the ravishing notes of Josef Strauss’ The Blue Danube.

The station embodied life in space as the futurists of 1968 saw it: all-white physical environs, iconic red Olivier Mourgue lounge chairs, and an international cast of characters devoting themselves equally to science, business and hospitality, while they awaited scheduled departures for other destinations.

The business of space has always been a delicate balancing act, poised between the intense romance of popular imagination and decidedly unglamorous mechanics that it takes to bring vision into reality. The prosaic details include technology, capital outlays, human organization, the marshalling of resources, and legal or policy frameworks.

During the period when Arthur C. Clarke co-wrote 2001: A Space Odyssey with the film’s director Stanley Kubrick, the authors had more than imagination behind them: Peak-year funding for the U.S. Apollo program reached four percent of the American GDP, an extraordinary financial commitment and the tangible tip of a huge mobilization of public enthusiasm.

The Business of Space

Now, the business of space is in fashion again — or at least in the news. In February 2018, the Trump administration announced plans to privatize the International Space Station (ISS) operations beginning in 2025. Three private space companies led by high-profile businessmen — Elon Musk’s SpaceX, Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic and Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin — are proclaiming ambitious public goals and even more ambitious timetables.

Derek Webber, author of The Wright Stuff: The Century of Effort Behind Your Ticket to Space, has been to this rodeo before. In 2010, he was Vice Chair of Judges for the Google Lunar XPRIZE competition, the latest in a line of scientific competitions designed to push the frontier of space travel.

Webber has been a long-time advocate for space tourism, conducting original market research and contributing to the development of regulations via various working groups associated with the regulators such as the FAA’s Office of Commercial Space Travel.

“I was forecasting 2012 as the start date for the sub-orbital space tourism business,” says Webber. “It was particularly exciting in 2004, during the Ansari XPRIZE competition, when commercial sub-orbital space tourism seemed just around the corner, but here we are, some 14 years later, still waiting.”

The re-release of 2001: A Space Odyssey gave Webber the opportunity to compare the vision of 1968 with the realities of 2018. He is well aware of the power of visionary pull — and its practical undercarriage.

“I saw that movie and I loved it. I’m still carrying the torch,” he says.

“But I think in practice things are going to be more nuts and bolts than we saw in ‘2001.’ The reality of things is less exotic,” he added, reflecting on a favorable regulatory environment, ample funding and recurring peaks of interest.

When I look at a television series with a sequence of a space vehicle under repair, with astronauts in pods buzzing around scaffolding,” says Blachman, “I want to know who provided the worker’s comp.”

At the Intersection of Capital and Technology

Amir Blachman is well positioned to consider nuts and bolts. As Vice President of Strategic Development at Axiom Space, he leads the financial planning, funding and growth strategy of a company that currently provides astronaut training services and is working towards operation of the world’s first private, international commercial space station when the ISS is decommissioned in 2024. Blachman’s own professional background includes the U.S. Air Force and the investment management industry.

“When I look at a television series with a sequence of a space vehicle under repair, with astronauts in pods buzzing around scaffolding,” says Blachman, “I want to know who provided the worker’s comp.”

Blachman takes the longitudinal view of an evolving industry, marking off key inflection points in an accretive build-up of capital infusions, practices, technologies, processes and infrastructure. One of the most apt historic analogies, Blachman says, comes from Dr. Howard McCurdy’s 2013 research report, The Economics of Innovation: Mountaineering and the American Space Program, which in nearly forensic detail examined the parallel logistical challenges and economic paths of climbing Mount Everest and crewed space flight.

“Climbing Everest and going to space are expensive and have risk,” says Blachman, “and they’re both motivated by science, commerce, national prestige and a personal desire for challenge and exploration. The similarities are uncanny.”

A Six-Phase Development Model

McCurdy chronicled a ten-fold reduction in the cost of expeditions in the first 90 years of climbing Everest, and parallel falls in mortality rates. Building off his work, Blachman outlines a six-phase development model, in which:

1) Innovation leads to cost reductions;

2) Lower costs encourages entrepreneurs to enter;

3) The promise of profits encourages investors to enter;

4) Profits lead to competition;

5) Competition produces further innovation, cost reduction and scale;

6) Price becomes low enough so ordinary people can afford it.

“In terms of space we are at step three and it will probably be another twenty to thirty years before we get to the point where ordinary people can afford it,” says Blachman. “But it is happening.”

The emerging ecosystem of actors for the business of space, says Blachman, will still include incumbents like governments and their space agencies, as well as traditional “cost-plus” defense and aerospace private contractors such as Boeing.

An additional slice will be made up of an emerging mass of micro-gravity innovators, who are building the companies focused on manufacturing and research in space. Rounding out those segments are “intrapreneurs,” in-house entrepreneurs who are developing the services and technologies used in low Earth orbit, or providers of additive manufacturing sub-platforms.

The Not-So-Hidden Hand

In The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith coined his “invisible hand of the marketplace” concept as the ultimate guide to economic history. But in space, the highly visible hand of the U.S. government has been and still remains the prime agent for space-related developments.

The government made the massive initial investments in space activity; the ISS alone is reported to have cost $100 billion to build. Some industry observers say NASA’s switch from purely cost-plus contract bidding to fixed-fee bidding, was as significant a financial advance for the industry as SpaceX’s successful reusable launch vehicle was a technological advance.

Dr. Peter Martinez is keeping a wary eye on governments and commercial players for their effects on another invisible hand: the treaties and regulations which currently set the rules for all parties. Martinez is the Executive Director of the Secure World Foundation, a private operating foundation that works with governments, industry, international organizations, and civil society to develop and promote ideas and actions to achieve the secure, sustainable, and peaceful uses of outer space. He recently chaired the U.N. Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space Working Group on the Long-term Sustainability of Outer Space Activities, which was tasked with producing voluntary space sustainability guidelines for States and space actors.

“There are new actors coming into the space arena, people who traditionally don’t have this background,” says Martinez, speaking of the diverse individuals in what some call the New Space movement. “These are people who are personally passionate, like Musk, not content to sit around and wait for national space programs to develop the capabilities to take people to the moon or to Mars or whatever. They’re actually going to go out there and do these things themselves.”

Can Space Resources be Appropriated?

From Martinez’s perspective, the commercialization of space is opening up new questions, including “can space resources be appropriated?” Under the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, the first and most important of the five U.N. treaties that govern space-related law, the moon and asteroids are not subject to the territorial claims of any nation.

Three years ago, however, the U.S. upped the ante, with its “Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act of 2015” (“Spurring Private Aerospace and Competitiveness Entrepreneurship Act”), opening the doors for private parties to “engage in the commercial exploration and exploitation of space resources,” excluding biological life. According to Martinez, the Act was careful not to assert U.S. sovereignty over any terrestrial body, but it does allow private entities rights to “extract, own, transfer and sell materials derived from other celestial bodies.”

For now, the legal regime that governs outer space is largely bearing up under the stresses and strains of many new players on the scene, according to Martinez. The Outer Space Treaty, which celebrated its 50th anniversary in October 2017, still provides the international legal foundation for all outer space activities carried out today.

Space Law-Making

Subsequent to the adoption of the Outer Space Treaty in 1967, four other treaties were adopted that address issues such as liability for accidents involving space objects, the registration of space objects, the rescue of astronauts and return of space objects that land on Earth, and the exploration and use of the moon and other celestial bodies. Following this period of space law-making in the 1960s and 1970s, the international community has focused on the implementation of the treaties, supplementing them with additional “soft-law” mechanisms, such as principles and guidelines that address topics such as remote sensing, space debris, and the use of nuclear power sources in outer space.

The field of space law has largely focused on implementation issues arising from the growth of space activities. There are still many open, unaddressed issues, he says, for example the lack of an international agreement on delimitation between airspace and outer space.

“The real danger, of course, is that the reality of development will outpace the ability of regulators to keep up,” he says, outlining scenarios in which commercial entities, looking for the most favorable regulatory environment, could engage in “regulation shopping” and choose to put themselves under the legal auspices of nations with unsophisticated legal systems.

Other legal developments stem from the fact that space is no longer purely the province of science, or even regarded as “somewhere out there,” says Martinez. Citing GPS, he says, “Space is part of the plumbing of everyday life. Most people are unaware of the critical role that space plays in our daily lives. If space were to go down for one day, it would be catastrophic — for stock exchanges, elevators, airports. The glamour is there, but we’re so used to it, we don’t see it anymore.”

The future is always the projection screen on which we throw our plans for today.”

Awareness and Attitudes

While government-sponsored agencies like NASA may be retreating from crewed space activity, government hasn’t entirely abandoned the field. Military imperatives have always played an enormous role in the evolution of the space industry, their public profile whether obvious or not, their under-the-radar initiatives never disappearing entirely. When Vice President Pence announced the formation of the U.S. Space Force, he called it “an idea whose time had come.” The Vice President went on to say, “It is not enough to merely have an American presence. We must have American dominance in space.”

Astronomer Lucianne Walkowicz invites audiences to simply be aware of the underlying attitudes in terms such as “dominance.” Walkowicz, based at the Adler Planetarium in Chicago, straddles the professional worlds of hard science, education, art and philosophy. She’s the author of Fear of a Green Planet: Inclusive Systems of Thought for Human Exploration of Mars, and speaks frequently on the implications of space-related imagination and futurism.

As just one example, she points to magazine illustrations envisioning man in space published in popular American magazines during the 1950s. Those illustrations had outsized impact on the public imagination then, and their influence can still be found in the marketing materials of commercial space companies today. A lot of those images are rooted in the military history of space, notes Walkowicz, with hierarchic organization of missions or crews.

Part of a Larger Ecosystem

“The reason that they are expressed that way visually is that they’re expressions of different philosophies about how human beings should live, not only in space, but here on Earth,” she says. “The future is always the projection screen on which we throw our plans for today.”

Walkowicz does a lot of public communication about the implications of ideas on a day-to-day practical basis. For more specialized audiences, like her astronomy graduate students, she delves into the ethical implications of professional development, and the responsibilities of science and scientists.

Against very real facts such as the discovery of frozen underground bodies of water on Mars, Walkowicz helps peers and generalist audiences alike look differently at grand schemes such as “terraforming” planets like Mars to make them more like Earth and suitable for human colonization.

“If it was possible to do a large-scale global engineering project that transformed Mars into Earth, we wouldn’t have climate change here on Earth,” says Walkowicz.

“Astronomers need to be aware they are part of a larger ecosystem. Technology is not separated from the rest of human endeavor, and it shouldn’t be,” she says. “We can look at our own history and see myriad examples of places where we pushed ahead in areas and did not consider the impact prior to going ahead. That, generally speaking, has turned out badly.”