The Evolution and Impact of Einstein

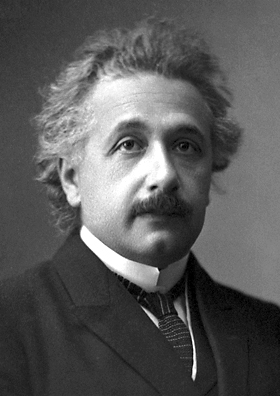

Walter Isaacson, acclaimed biographer and onetime CNN chairman personalizes history’s most famous genius in his new biography about Albert Einstein.

Published May 25, 2007

By Adrienne Burke

Academy Contributor

Having already penned a bestselling book about the life of Ben Franklin and another on Henry Kissinger, Walter Isaacson, CEO of the Aspen Institute, became interested in Albert Einstein as the subject of his third biography while working as managing editor at Time Magazine.

“We were looking at who should be person of the century in the mid ’90s and I became more and more convinced that it should be Einstein because it was a century of science and technology,” Isaacson says. “Obviously the two great scientific theories, quantum theory and relativity, are born out of his papers in 1905, but also [his work led] to a century of technology in which you can see his fingerprints on everything from atomic power to lasers to photoelectric cells—even the microchip.”

Isaacson says he also saw Einstein as a representative of people who left oppressive places, fleeing the Nazis or the Communists during the last century, in order to come into places where there is more freedom. “His life is a testament to the connection between freedom and creativity,” Isaacson says.

In a prelude to his upcoming speaking engagement at the Academy, the author discussed his research on Einstein.

Your educational background is not in science, but you do a fantastic job of explaining Einstein’s theories in a way a lay reader can understand them. How did you do that?

First of all, I love science. I was one of those geeks who always used to enter what was then the Westinghouse Future Scientists of America contest. Unfortunately, I was also among those who never won the big prize. But I kept that sense of wonder and I believe that those of us who are not scientists should be able to appreciate and grapple with science just as we do with great music or theatre. The joy and wonder of creativity is something we should embrace as a society even when it’s in a field we don’t know as much about.

I also had a lot of great help from scientists like Murray Gell-Mann, Brian Greene, Lawrence Krauss, Doug Stone at Yale, and Gerry Holton up at Harvard, who helped me with the science. And I took a couple of math courses to make sure I could understand the tensor calculus. But I tried to do a book that’s geared for the non-scientist. There are other great books for those who want to delve down deeper into Einstein’s science.

You note in the book that there are those who have suggested that Einstein’s first wife, Mileva Maric, contributed more to the development of his theories than she’s credited with, but you seem to conclude that the work was purely his own.

I don’t think it was purely his. I think the conceptual leaps were his. The idea of the relativity of simultaneity, which is at the core of the special theory—I think he does that while walking with his friend from the patent office, Michele Besso.

But I do think she helped check the math, she served as a sounding board, and, perhaps even more difficult, she put up with him when he was not the world’s best husband in 1905 and that period. I think she’s a great pioneer in science, but as we look at the papers and discover day by day what he was writing, what he was saying, who he was talking to, I don’t think it does her justice to exaggerate her credit to these things.

I think we can do her justice and show her the respect she deserves by showing what a pioneer she was in the field of science for women, how important she was to Einstein’s life at that point, but not try to say that she came up with the concepts behind the theory of relativity.

Everyone is fascinated with Einstein’s view of God. You call him “the mind reader of the creator of the cosmos.”

He always tried to figure out the elegance and the spirit manifest in the laws of the universe and he says, for him, that’s his cosmic religion. Both during his lifetime and nowadays, both sides of the religious argument try to compete for Einstein, whether it’s the people who are strongly atheist or the people who are fundamental believers. They all quote Einstein out of context.

It takes an entire chapter of my book for me to try to put it all in context, and it evolves over the years. But at age 50 he believes in what you might call a deist or perhaps pantheist conception of a God whose spirit is manifest in the laws of the universe, not a personal God who intervenes in our lives.

I think what’s important is to watch him wrestling with that concept and to see how humbled he is, because, as he puts it, our imaginations are far too small for the vastness of these eternal questions, so we just feel our way. And I think it might give pause and some humility to those on both sides of the argument who think they’ve solved this argument to know how Einstein wrestled with it and to see how his views evolved over the years.

Are there things that you reveal in this book that had been previously unknown about Einstein?

I think there’s a lot in the personal letters that became available just in the past 12 months … that shows the struggle in particular when he’s doing general relativity, struggling against the militarist times in Berlin where he’s a professor, becoming a pacifist, having these custody battles where the kids are being used as pawns between him and Mileva, and racing against others to get the field equations of gravity right for his general theory. To me that’s an absolutely thrilling tale that we couldn’t tell until the latest opening of the papers.

About the Author

Walter Isaacson has been the President and CEO of the Aspen Institute since 2003. He has been the Chairman and CEO of CNN and the Managing Editor of Time Magazine. He is the author of Benjamin Franklin: An American Life (2003) and of Kissinger: A Biography (1992) and is the coauthor of The Wise Men: Six Friends and the World They Made (1986). His biography of Albert Einstein – Einstein: His Life and Universe – was released in April 2007.

Also read: From Successful Actors to Impactful Science Advocate