A New Perspective to Sustainable Reef Restoration

It will require a group effort from scientists, artists, and the public to protect the planet’s vital but endangered coral reefs.

Published September 30, 2024

By Nick Fetty

Digital Content Manager

Science and art merged during The Art of Sustainable Reef Restoration in the Age of the Anthropocene- Cuba and Beyond event at The New York Academy of Sciences (the Academy) on September 19, 2024. The event was presented by the Academy and sponsored by Kasirer and Benefit Plan Manager

Nicholas Dirks, president and CEO of the Academy, greeted guests and introduced the moderator and three panelists:

Meet the Panel

- Emily Driscoll, MA: Driscoll is an Emmy Award-winning science video producer and the founder of BonSci Films. Her 2014 film Invisible Ocean: Plankton and Plastic featured artwork from Mara Haseltine.

- Fernando Bretos, MSc: Bretos is a marine biologist and National Geographic Explorer, a National Fellow at The Explorers Club, and President of the Board of Trustees of SECORE International. His work explores the science behind creating genetically stronger strains of coral using coral larval propagation techniques.

- Tom J.F. Goreau, PhD: Dr. Goreau is Director of The Global Coral Reef Alliance. His research examines “biorock,” a restoration technique that utilizes a novel way to restore corals with light electrical fields of negative electricity using the anodic-cathodic process on metal structures which then accrete calcium carbonate, a property that produces coral skeletons.

- Mara G. Haseltine, MFA: Haseltine is an artist and activist with The Explorers Club and The Ocean Foundation. Her work explores the link between our cultural and biological evolution.

“We are an academy of sciences in the broad sense which is to say that we look at the impact of science on society. And we think about the relationships science has with just about every part of life, including, of course, the arts,” said Dirks. “Which is why we’ve been so pleased to have some of the art by Mara Haseltine on display.”

Joining Forces, Utilizing Diverse Skillsets

The event took place prior to Climate Week NYC, “the largest event of its kind to address climate change,” according to Emily Driscoll, the event’s moderator.

She went on to say that monumental challenges like climate change can only be tackled if society joins forces and leverages diverse skill sets. “We need to make the invisible visible. Inspire curiosity. Offer solutions. We need to combine science and art. Tonight we have the privilege to do just that.”

Some scientists describe coral reefs as “the canary in the coal mine” in terms of anticipating the detrimental impacts of climate change. Coral reefs are important to the sustainability of the planet because they not only create shore protection, but they also promote fishing and ecotourism locally.

Fernando Bretos, MSc, then discussed the immense strides made in coral restoration over the past two decades, particularly in the Gulf of Mexico. While advances are being made, he acknowledges more work needs to be done within his subfield of asexual coral restoration, which he compared to gardening.

“It’s taking cuttings of corals, moving them into nurseries, and replanting them,” said Bretos. “But these are all clones, so they’re lacking the genetic diversity, the resilience, to cope with so many changes. And unfortunately, the Caribbean is getting hit hard.”

A “Hope Spot for Innovation”

Despite the challenges, Bretos described the Caribbean as a “hope spot for innovation” because of all the scientific ingenuity being forced by the urgency of the threats. He then shifted his focus to sexual restoration.

“I think the world needs more sex in general,” Bretos said, met by laughter from those in attendance. “And corals need more sex because the problem with corals is that because they are so sparse, especially in the Caribbean, their natural ways of reproducing aren’t as effective.”

Much of his work in asexual (fragmental) coral restoration began around 2015 at Guanahacabibes and Jardines de la Reina (“Gardens of the Queen”) National Parks in Cuba. He and his team’s findings proved to be promising with Bretos describing it as “probably the most successful asexual coral restoration project in Cuba.”

Following a Dream

Separate from his work in asexual restoration, SECORE International, of which Fernando Bretos serves as President of the Board of Trustees, has developed a technique known as coral seeding. This involves speeding up the sexual process, or as some have called it “IVF for corals.” Such research, including a recent paper published in PLOS One, also suggests that survival rates for young polyps are higher with coral seeding than natural (unassisted) sexual reproduction.

Bretos said one of the greatest outcomes from this effort are the training techniques they are developing to help prepare the next generation of marine biologists. He was personally inspired by a young, aspiring marine biologist in Cuba named Ramón. Ramón is bucking the brain drain trend, common in many Caribbean countries, when young people either leave or never return to their home country after getting their education.

“I’ve been dreaming of doing this my entire life. My mother wants me to [move to Miami with her], but I’m staying because now I’m a marine biologist,” Bretos said, recalling his conversation with Raul. “Even though he’s going to make 30 dollars a month doing what he does, that’s enough for him to stay.”

Hotter Temperatures Coupled with More Hot Days

Tom J.F. Goreau, PhD spoke about his work with the Global Coral Reef Alliance, a non-profit organization for coral reef protection and sustainable management. His interest in marine biology is because of his father. The younger Goreau began accompanying his father for dives along coral reefs as soon as he could walk.

“I’ve been diving for 70 years on coral reefs,” said Dr. Goreau, adding that he’s explored reefs in the Caribbean, the Indian Ocean, and Pacific Ocean near Southeast Asia.

He said that part of the reason coral reefs are so endangered is because they’re highly susceptible to ecological threats. This includes high temperatures, salinity, pollution, mud, and more. He explained that scientists began observing mass bleaching of corals in the 1980s. At first, they struggled to pinpoint the cause but eventually realized it was a slight rise in temperature that had “such a dramatic impact.”

Not only was 2023 the warmest recorded year in human history, according to data from NOAA, but it was also the worst year for coral bleaching in the Caribbean. Dr. Goreau explained that the earth is experiencing longer durations of hotter temperatures. While the general trends are troubling, Dr. Goreau acknowledged that an area around the Bay of Matanzas on the north coast of Cuba, was “the only place [in the Caribbean] that did not get above lethal temperatures” in 2023. He said this was because of the way the currents move in this part of the ocean.

Biorock Coral Arks

One innovative way scientists are trying to preserve coral reefs is through biorock coral arks. This approach involves electrifying corals using “a trickle of electricity so small you cannot feel it.” With this practice, scientists can regrow reefs of any shape or size in the ocean. Research on this practice has been promising in areas such as settlement diversity, growth, survival, and resistance to stress.

“It’s the only method known that does that and the reason is that all life is electrical. All life is based on a little flow of electricity,” Dr. Goreau explained. “If you’re in the right range it’s [biologically] beneficial and healthy for you.”

Dr. Goreau and his research team build the scaffolding for these biorock structures from steel. They then grow solid limestone rock over the steel bars by applying electricity. The rate of growth is roughly one to two centimeters per year. The process is deliberately slow because this enables them to develop a material that is two to three times harder than concrete. Because of this durability these manufactured apparatuses, which look like cages, can better withstand wave stresses and other environmental factors.

“These structures not only are growing faster than sea level rises but they’re also self-repairing,” said Dr. Goreau. He explained that in one instance a passing boat damaged one of the structures, but within a year the limestone had grown back, repairing the damaged section.

Naturally Regenerating Beaches

This technique proved successful in the Maldives in 1998 when a mass coral bleaching event wiped out nearly 99% of coral reefs in the region. The corals around Dr. Goreau’s biorock structures managed to survive.

Moreover, it prevented bleaching for 18 years until 2016 when the power was cut off. This resulted in a die off of the reefs that Dr. Goreau had worked hard to revitalize. Also in 2016, he led a similar effort restoring corals around Indonesia. In both instances, the beaches in these areas that had been eroding because of the lack of reefs, began naturally regenerating. This is the only known method for naturally restoring sand beaches, which is less expensive and erosive than seawalls.

“What we can do with this technology is we can use solar power to grow back reefs, protect shorelines, generate mariculture, and protect our marine resources that we’re about to lose on a large scale,” Dr. Goreau said. “The technology is there to do it if there’s the funding and the will.”

An Artist’s Touch

Mara G. Haseltine, MFA, then took the podium to talk about her art. One feature of her work is her use of sustainable materials such as the biorock technique developed by Dr. Goreau, with whom she’s been working for more than two decades. She wanted to combine this technique with other means of sustainable reef restoration.

“I think that infusing art and poetry into the field sciences is crucial if we’re going to make a big difference in climate change,” Haseltine said.

Haseltine’s work embraces the concept of “geotherapy” a term coined by a panel of scientists in Leon, France in 1992. For her, geotherapy is a call to action to help save the planet, “for not just corals, but all sorts of things.” As part of her exhibition, Haseltine placed a thought bubble over the Academy’s bust of Charles Darwin, pondering “Geotherapy, an elegant adaptation for the Age of the Anthropocene… A poetic shift towards a symbiotic relationship with our shared biosphere… this would effect the evolution of ALL life on the planet. Hope it works!” Darwin was an early honorary member of the Academy.

Blueprint to Save the Planet

Haseltine then discussed her works currently on display in the Academy’s lobby as part of a project she’s calling Blueprint to Save the Planet: 1 Coral Reefs. Her exhibition encompasses 17 individual works, including 2D and 3D pieces.

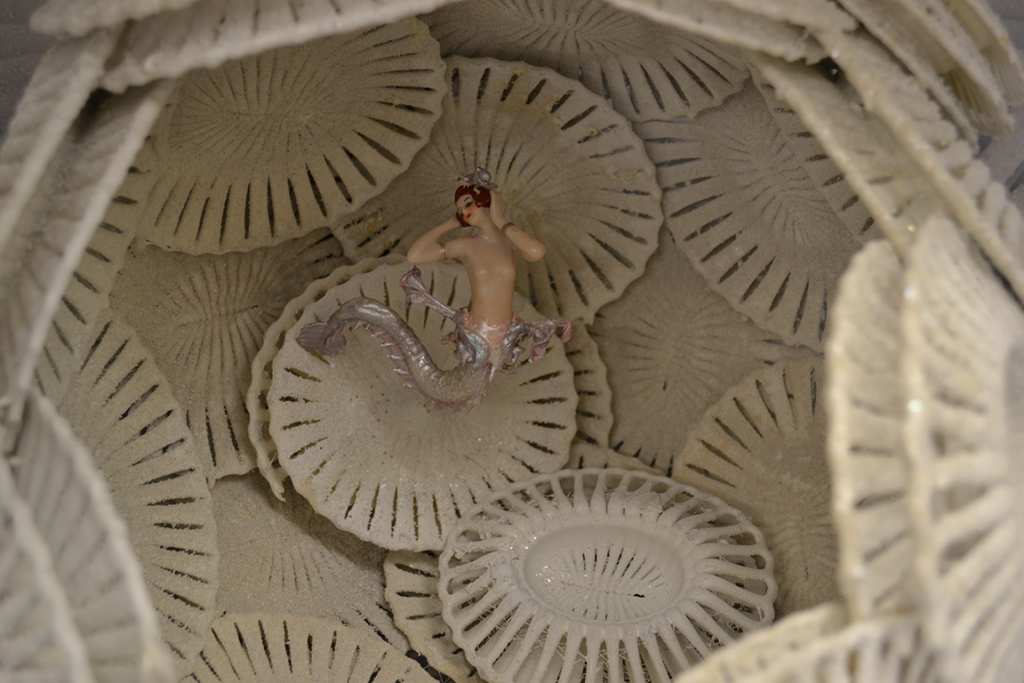

Her Rococo Cocco Reef Model is one of the highlights of her impressive exhibition. The piece, roughly 27 cubic feet in size, is composed of crushed coral (coccolithophore) skeletons. Coccolithophore skeletons play a positive role in carbon sequestration.

Another highlight of the exhibition is her Plankton Pod Coral Nursery, largely inspired by Dr. Goreau’s biorock idea. It also brings in elements around Bretos’ work in larval propagation. In addition to helping with reef restoration, she also hopes that her miniaturized model can serve as a learning tool for students.

A post-discussion reception included organic wine featuring Haseltine’s art on the label donated by Perkins Harter Vineyard. In closing, Haseltine addressed how she measures success on her efforts that combine art and science.

“For me, success would be [increased] awareness. The fact I’m sitting here and talking about this is part of that,” she said. “Not only does this work [promote] incredible science, but [advancing] ecotourism and building up economies are also factors.”

Can’t make it into the Academy? Take a virtual tour of the exhibition led by the artist herself.