The Art and Science of Human Facial Perception

The New York Academy of Sciences’ Barbara Knappmeyer applies her expertise in human facial perception to her analysis on an exhibition of the late artist Chuck Close.

Published June 4, 2024

By Dorian DeBose

Administrative Assistant, CAO and SVP, Education

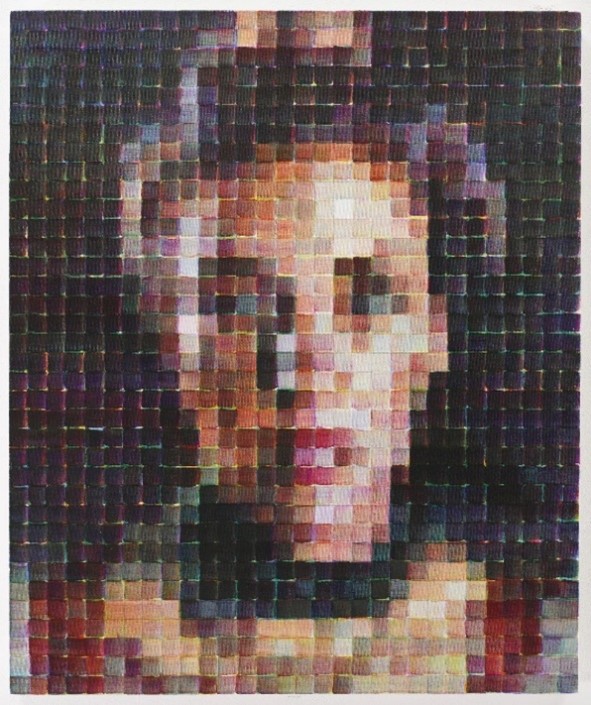

Recently the Pace Gallery in New York City, unveiled “Red, Yellow, and Blue: The Last Paintings,” an exhibition devoted to the work of the late artist, Chuck Close. The exhibition – the first of Close’s work since his death in 2021 – showcased the final evolution of the great artist.

Close’s paintings play with a viewer’s perception. His later work consists of painted squares that together reveal brilliant portraits. The painting’s resolution ranges drastically – some are photorealistic, others more abstract – yet they still register undeniably as human.

Human Facial Perception

Barbara Knappmeyer, PhD, Associate Director of Fellowships for The New York Academy of Sciences, knew Chuck Close for over 20 years and was fascinated by his paintings long before then. His work had a clear overlap with Dr. Knappmeyer’s own area of study: human facial perception.

“He was doing this very intuitively,” Dr. Knappmeyer said. “I don’t think he would have been able to explain to you in scientific terms what it does to your visual perception system. [But] he knew how to create it.”

Dr. Knappmeyer contributed an article to the journal regarding Close’s final exhibition. In it, she elaborates on the science of how work like Close’s challenges the visual system. We take in enough information from viewing the paintings at a distance to construct a face in great detail, then have our assumptions dashed upon closer viewing.

She writes: “Human visual perception is a very active process. At every step of the way—from the retina via the optic nerve to the primary visual areas of the brain on to the high-level cortical areas—the signals get translated, filtered, amplified, or deemphasized, combined with preexisting information, and compiled with information from other brain regions. All of this active signal processing happens automatically in our brains within split seconds and leads to a seemingly instantaneous perceptual experience. We like to believe that what we see is the truth, but it’s just our perception of the truth.”

Recognizing Faces, Sensing Emotion

Humans are extremely adept at identifying faces. Recognizing familiar faces or sensing the emotion in another person’s expression are vital traits for humans as a social species. Even newborn babies can pick up on the roughest outline of a face.

“When a baby is born – literally just opens their eyes – and you show them a pattern that has two dark dots on the top and one dark dot and on the bottom (the basic template of a face), they will look at this more than at anything else,” said Dr. Knappmeyer. “They already have some built-in detector that draws them to faces more than anything else.”

Indeed, it is because humans are so good at recognizing faces that art like Close’s is so riveting. It engages our most base assumptions then challenges us to delve deeper. Illusionists of all kinds use this trick. From magicians who use sleight of hand to exploit the visual system to artists like M.C. Escher who create impossible structures through depth; making the audience think twice about their own observations can lead to some very interesting art.

The Science of Illusions

And the science is just as interesting. Illusions that challenge our visual perception are a rich area of exploration for both artists and scientists. Most optical illusions have been studied endlessly, according to Dr. Knappmeyer.

“Some scientists have made their whole career out of investigating this intersection,” she said.

Michal Rovner’s work “Data Zone, Cultures Table #3” depicts what appears to be a culture growing in a petri dish, which is revealed to be masses of people upon inspection. This work uses the audiences’ assumptions against them to create a powerful illusion.

“These are people, something that we are very familiar with, but we are not familiar with that perspective from so far away and from high up,” Dr. Knappmeyer said. “That’s another interesting example of how our brains constantly make assumptions on what we see and when those assumptions are disrupted, we’re surprised.”

Dr. Knappmeyer also highlighted the work of Richard Serra, the late sculptor whose massive structures often appeared to be on the verge of collapse.

“How could they be built the way they are and still be stable?” asked Dr. Knappmeyer. “I think it sort of plays with our assumptions of gravity and the world around us.”

The Use of Light

The final artist Dr. Knappmeyer mentioned is James Turrell. Turrell’s work uses light to create structures and textures where there is only empty space.

“Even when you come close, it’s hard to know this,” Dr. Knappmeyer said. “You realize there is no surface there, and all it is, is diffused lighting, but so brilliantly done that your brain tricks you into believing that there is a surface.”

For Dr. Knappmeyer, knowing the science behind the illusions adds another layer of depth to Close’s work without tarnishing the appeal. As she wrote in the conclusion of her essay in the journal for the exhibition: “It makes it even more magical to me.”